theallelectricsmartgrid

LaMeJuIS

Video Manual

Find video tutorial here. Note: the front panel has changed and in particular the switches have been transposed. What once were rows are now columns.

Overview

LameJuis is a module which takes some gate inputs and produces three interlocked, evolving melodie. LameJuis is modeless and stateless, meaning the values on the inputs and positions of the many switches and knobs completely determine the output. The melodies it creates seem to imply a strong sense of harmonic progression, tonal center and song form despite knowing nothing of scales and chords (not even the chromatic scale). These melodies are generated using three simple ideas, none of which are hard to understand, but each of which is (to my knowledge) outside the mainstream of Eurorack sequencing. The ideas are

- Euler’s Lattice: Laying out notes in a grid such that nearby notes are strongly related.

- Logic Matrix: Using a matrix of logic operations to select notes on this grid.

- Co-Muting: Selectively ignoring inputs to the logic matrix in order to generate multiple related melodies.

The Theory

For people who only care about traditional western 12-notes-per-octave music, most Just Intonation aspects of this module can simply be ignored. However, JI gives some lovely insight into the structure of harmony by organizing pitches in a multi-dimensional lattice, and exploiting this structure for composition creates pleasing melodies. The small tuning improvements are secondary, although it gives the option to explore more out there sounds to those who wish.

In many sequencers, notes are organized numerically, by frequency, so notes close in frequency end up near each other. In order to only pick “good” notes, the allowed frequencies are then quantized into some pre-determined scale. Another posibility is to sort notes so that harmonically related notes are near each other. Doing this in one dimension by stacking fifths gives the well known circle of fifths, which has a specific sort of sound, but what happens when we lay out notes in two dimensions, with one axis going up by fifths and one axis going up by major thirds, like so:

| C# | G# | D# | A# | E# |

| A | E | B | F# | C# |

| F | C | G | D | A |

| Db | Ab | Eb | Bb | F |

Because going up a perfect fifth and then a major third is the same as going up a major third and then a perfect fifth, we get a well defined grid of notes. Whats more, simple geometric shapes tend to form nice chords (go find your favorites, major and minor triads are triangles) and nearby shapes tend for form nice chord progressions. And since the notes are laid out in 2-d, two patterns taking a small number of values can address all 12 notes, and if the ranges of those values are constrained or related in some way, the notes will have some notion of a key, or at least make some level of harmonic sense.

So the game becomes this: find a way to draw patterns on that grid. Thats where the logic comes in. A few logic operations (on the same inputs) are assigned to different intervals. Count up the number of “high” gates for each interval and get a position on the grid.

One more note, (and this can mostly be ignored except by people who love tuning): because the intervals are laid out on a grid where the relationships between notes are very well defined, it makes complete sense to use “Just Intervals” instead of 12-EDO intervals. That means the frequency ratio between a note and its neighbor to the right is exactly 3/2, and its neighbor to the top is 5/4. Don’t worry, its easy to make sequences where very pure tuning won’t really sound wrong. The pure intervals can produce a delightful “buzzing” effect in many cases, or sound “very xenharmonic” if thats what you’re going for. For musicians who are happy thinking just about 12-EDO, this detail can simply be ignored, or right-click and select ‘12-EDO mode’.

Inputs

LameJuis has six gate inputs on the left side of the module labeled A-F. Each input is normalled to a divide-by-2 clock divider (flip flop) of the input above, meaning you can run the entire sequencer on a single clock at the A-input and get cascading clock dividers the other inputs. Running in this mode can feel a lot like a 64-step sequencer, but by sending other sorts of gate patterns you can get all sorts of behaviors out of LameJuis. Sending a trigger to the reset input (left side of the panel) will reset the clock dividers for unplugged inputs the next time the input above goes high.

Quick note about conventions: although you can plug any gate patterns into LameJuis you want, things become easier to explain/motivate if we assume the top inputs are changing faster than the bottom inputs. Then we can say the top inputs represent melodic movement while the middle inputs represent chord progression and bottom inputs represent song form (since melodies move faster than chords, which move faster than song form). This is, of course, just a thing in our brains, but our brains are so used to hearing music organized in this way we might as well exploit this hierarchy. From the perspective of how the sequencer actually works, all six inputs are identical.

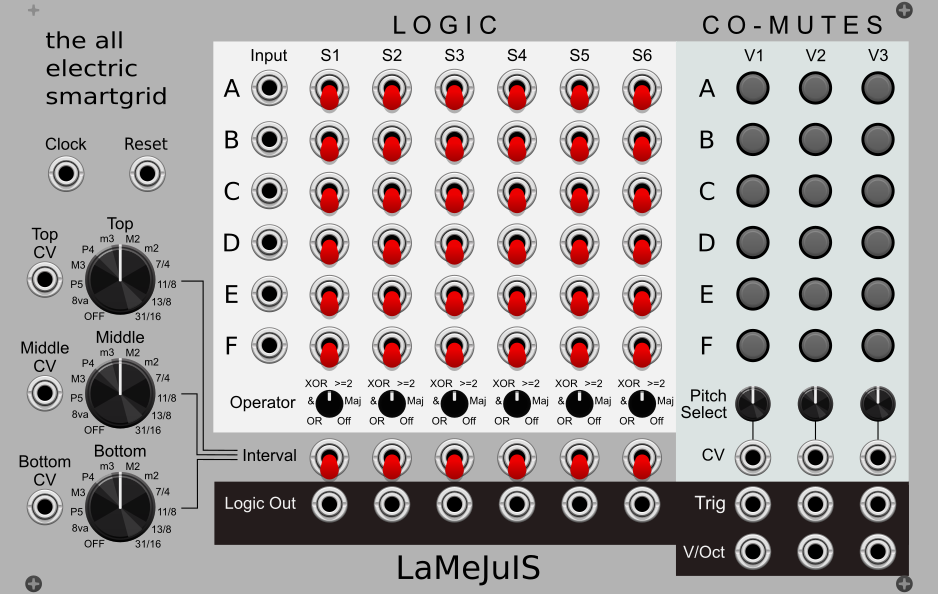

Logic Matrix

The six identical inputs are processed by six identical logic operations. Each operation is a column in the large switch matrix in the middle of the module. The first six switches (each column), labeled A-F, determine which inputs are processed by the operation. The switches are three position switches. In the “up” position, the input is part of the operation. In the middle position, it is ignored. In the down position, the input is “negated”, so treated as low if its high and high if its low. The knob (knobs at the bottom of each column) selects the logic operation. So, for instance, if the first switch is up, the third switch is down and the rest are neutral, the operation will apply to A and (NOT C). The gate output of each operation is available at the corresponding Logic Out output (bottom of each column). The outputs are unaffected by melodic parameters like co-mutes and intervals (which will be discussed later), so already LameJuis is a highly configurable six-in-six-out logic module!

You may notice some operations like NAND are not included. This is because it is not needed, given the ability to negate individual inputs. For instance, A NAND B is the same as (NOT A) OR (NOT B). This is called De-Morgan’s law and can be fun to think through if you haven’t seen it before. Similarly, there is no CV over the state of the matrix, but instead variation comes from logic operations changing their response as slower changing gates go from low to high and back again. For instance, A AND F will go up and down as A changes when F is high, but as soon as F goes low the gate will stay low until F comes back. The logic matrix becomes surprisingly intuitive after you play with it a bit, and its very easy to just start flipping switches and see what comes out. You can see the tips and trick section for tips and tricks.

12-EDO Mode

If you don’t want to learn what a comma is, or if you want to use LameJuis alongside a regular 12-EDO sequence, right-click and select 12-EDO-mode. This will make the interval selector pick 12-EDO intervals, and commas (potentially harsh sounds when jumping between far-away spots in the lattice) will disapear.

Intervals

Each logic operation is finally routed by the final three-position “Interval Select” switch (below the logic select knob) to one of three intervals. These intervals are determined by the three “Interval” knobs and their corresponding CV input (left side of the panel). When the operation outputs high, the pitch moves up by the selected interval (before co-muting), and is unaffected otherwise. Let’s say the top interval is P5, and the middle interval is M3. If there are two matrix rows with high outputs with interval select set to P5, and one row with high output with interval set to M3, the pitch produced will be two fifths and one third up, which happens to be a major seventh. To say another way, for each of the three possible positions of the interval selector switch, count the number of logic operations which are currently high, and go up by that interval, that many times.

Sounds confusing? It isn’t, but it is hard to explain in words. Try watching the demo video if it’s not clicking.

The value of the “Interval CV” is volt per octave input is added to the interval from the knob. Thus if the knob is “Off”, the Interval CV is used (so 12 EDO intervals can be supplied, or other just ratios or microtonal generators, or an offset from a slider).

The interval knob is arranged so more familiar ratios are found on the CCW side, and more esoteric intervals on the CW side. The intervals labeled in familiar ways are very close to western 12-EO intervals, but insead of irrationals like 2^{7/12} for a perfect fifth, Just frequency ratios like 3/2 are used. The following ratios are used:

- Off: 1/1: unison.

- 8va: 2/1: an octave up.

- P5: 3/2: the third harmonic, an octave down.

- M3: 5/4: the fifth harmonic, two octaves down.

- P4: 4/3: an octave up, a fifth down.

- m3: 6/5: a fifth up, a major third down.

- M2: 9/8: two fifths up, an octave down.

- m2: 16/15: an octave up, a fifth and a major third down.

- 7/4: The 7th harmonic, two octaves down. A flat minor seventh. Used in barbershop quarter, African and blues. Is a minor 7th in 12-EDO-mode.

- 11/8: The 11th harmonic, three octaves down. A half-flat tritone. Is a tritone in 12-EDO-mode.

- 13/8: The 13th harmonic, three octaves down. A neutral sixth. Is a minor sixth in 12-EDO-mode.

- 31/16: The 31st harmonic, four octaves down. A flat octave, used by La Monte Young. Is a major seventh in 12-EDO-mode. } The algorithm described above produces the melody that will come out if all co-mutes are tuned off (the middle position). And the melodies are quite fascinating. No music theory knowledge was used to construct them, no scale chosen, and yet the feeling of key, cadence, theme and variation arise naturally, depending on the switch positions. All we did was some binary logic and multiplied some fractions, yet the result definitively sounds like something. Depending on the configuration, melodies can go from quite familiar to exotic and xen, but there’s a quality about it which, at least to my ears, sounds musical.

Co-Muting

The above algorithm produces a single melody, which has a kind of jolted quality to it. Co-muting, and the associated pitch select knob and CV input, allow the single matrix described above to produce multiple interlocking lines while producing “smoother” melodies. The idea is as follows: start by assuming each input is a flip-flop of the one above. Then, for instance, you might hear A and B as a melody outlining a chord progression defined by C, D and E which changes from a “verse” to “chorus” based on F (these, of course, are just stories the composer tells themselves!). How can you create a bass-line from this? Well, we’re saying that the state of inputs (C,D,E,F) defines an implied chord that is played as A and B vary. As A and B vary, up to four pitches are played, so why not say the bass just plays the lowest of the four! Its an entirely simplistic idea, but it the results just sound right.

Co-muting generalizes this idea, and its very fun, performable and sequencable. Each of the three identical voices has six co-mute buttons (right side of the module, each column is a voice, each row is an input) and a pitch select knob (below the co-mute buttons) with CV input. For each voice, the values of the co-muted inputs are ignored. However, instead of being set to zero, the switch matrix is evaluated at all possible values of the co-muted inputs. The results are sorted, and based off the pitch select knob and CV one of the values is selected. For instance, if A and B are comuted, the matrix will be evaluated as if A and B were both high, both low, A high/B low, and B high/A low. If the pitch select knob+CV is fully counter-clockwise, the lowest of the four is chosen, while if fully clockwise the highest is chosen, and a middle value if its in the middle. In other words, among possible pitches which the matrix can produce leaving the non-co-muted values fixed and trying every possible co-muted value, pick the one which, from low-to-high, matches pitch select input+CV.

You can think of co-mutes as units of repetition. If using the default clock dividers as inputs, the highest non-co-muted input will determine the speed that voice will go. Higher co-mutes will cause repetition, and the pitch select knob/CV will change what gets repeated to the higher or lower option. Mixing co-mutes and sequencing the pitch selects can give a performer a huge number of highly coherent patterns to jump between, which are delightfully intuitive and yet unexpected. The pitch select inputs are polyphonic, allowing this method to scale to a huge number of voices (even just sending polyphonic offset yields a delightful ensemble of interlocked patterns).

The pitch select CV input has a 5 volt range. Comuting the leftmost few positions and sending a CV sequence into the interval intput makes LameJuis into an almost quantizer-like module. It isn’t quite: a quantizer picks the closest note while this picks from a fixed set of notes (which change when the un-co-muted inputs change), but it can take a 0-5V CV sequence and make a melody from it.

These pitches are available at the three voice outputs (bottom right corner). The trigger output produces a gate whenever these values change.

As far as I’m aware, this is a novel method for generated sequences. It isn’t as tricky to learn as it might seem, just play with the switches. Co-muting the left few inputs tends to produces harmonically coherent melodies. Voices with more co-muted inputs tend to play more sparesly. Multiple voices with the same inputs co-muted but different positions for the pitch select knob tend to form a bits of counterpoint and interlocked rhythms.

Polyphony

Sending a polyphonic input to the pitch select CV yeilds a polyphonic output for the corresponding voice’s pitch and gate outs. Send several sequences, or just several static offsets, to the pitch select CV in and get polyphonic outputs, sharing the co-mutes and pitch select knob offset. Even just static 0V and 5V signals can get nice independent counterpunctual lines.

Lattice Expander

The lattice expander won’t change what LameJuis is up to, but it can help with visualization. The X-coordinate is the top interval, the Y-coordinate is the middle interval. It will change the layout as the bottom interval changes (I can’t make it 3-d, sorry), and switch to cents if non 12-EDO intervals (or user-provided intervals) are used. Just slap it to the right of LameJuis and watch the lights blink.

For some glorious vocal harmonies using a similar visualization, check out Gary Garrett’s Flying Dream.

Randomizer

There are several randomizer functions, that will randomize parameters to different levels of chaos. Level 0 is the most tame, level 3 means flip all the switches and see what happens. Just right-click to find em.

Time-Quantize Mode

In this mode, switch and knob values are only read when an input gate or pitch select CV changes value. This can make it easier to time changes, especially when using the mouse. This mode is strongly recommended, because it prevents glitches, and makes LameJuis a very interactive instrument to play with. Find it in the right-click menu.

Clock Input

LameJuis can be computationally expensive, and can be very sensitive to things changing on slightly different frames. If this input (left side of the panel) is connected, steps will be skipped in less the clock in put receives a pulse. In some cases, a brief trigger delay can be very helpful.

Tips and Tricks

- Try lots of different inputs. Clock dividers, Euclidean rhythms, Bournouli gates, clocks with different phases and duty cycles all sound good.

- LameJuis can be somewhat sensitive to buffer delays on the gate inputs. If you get extra unwanted triggers, try using the clocking put.

- Use the “off” interval. Six equations is a lot, you can spare one to just use as an extra logic out/gate sequencer/end-of-cycle output. Or use it strategically to create a key change.

- AND logics will be low more of the time and sound like they add upwards motion to the melodies. OR logics will be high most of the time and add downwards motion to the logic. The more inputs are active the more “most of the time” is.

- XOR logics will be the most chaotic and unpredictable. For instance, A XOR F will invert the phase of A when F goes high. An XOR with many inputs will create a complex rhythm.

- Sequence the pitch select CVs. LameJuis can weirdly abosorb weirdness in the sequence, so changing parameters of the sequence, like the speed or skipping steps, tends to sound good.

- Use the logic outs for tambre, or for drums. It sounds very cohesive.

- Use Grande Microtonal Notes and the Interval CV input to get whatever EDO you want. For instance, say you want to compose in 19-EDO, but you don’t know anything about it. First use xenharmonic wiki to figure out that the the 11th and 6th step of 19 EDO correspond to the fifth and major third, respectively. Pick those on Microtonal Notes, route those to LameJuis’s Interval CV and and you’re ready to start –annoying your loved ones– making microtonal music.

- Play the co-mutes. Just try things with them. Right click and try randomizing them.

- You can use the interval CV in as a sort of transpose. AND of nothing is always true, so set one equation to AND, route to an unused interval, and that interval CV becomes a “transpose” input.

- Use the lattice expander. It just helps.

- General trick for modules like this, use 8Face. Find a pattern you like, mess it up and come back, all as performance gestures.

Thank you

Special thanks to guitarist and educator Jacob Pek who’s Fundamental Harmonic Motion class got me hip to these ideas, and is a constant source of inspiration.

Special thanks to my partner who doesn’t mind that I spend my time this way so long as I use headphones.

Special thanks to Dave Benham from Venom for making the front panel.